On Leonardo da Vinci and Gravity

In the last week or so, there’s been allot of conversation about Leonardo’s views on gravity, inspired by this press release from Cal Tech on a paper from their faculty. The topic’s made the rounds at Ars, Hacker news, and even the times, and been incorporated into wikipedia.

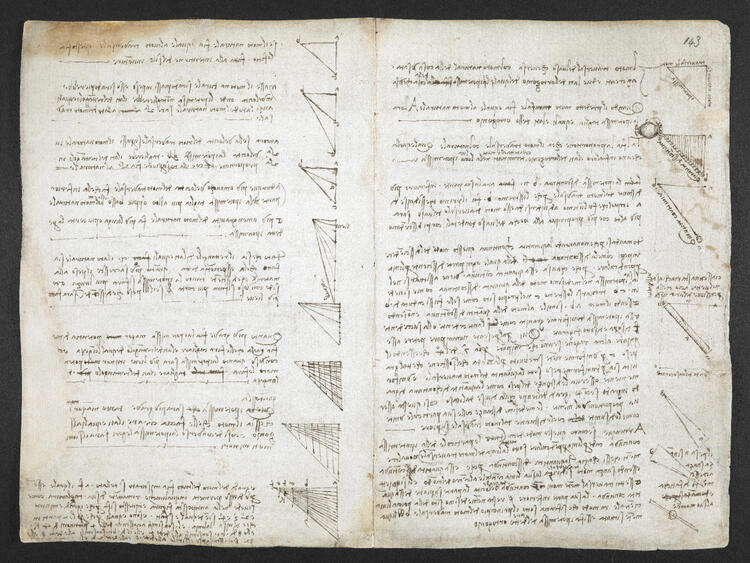

Leonardo’s manuscript being discussed is available from the British Museum, and page 143 in particular (shown below). Commentators seem to have looked into the actual article only superficially, perhaps because it is hard to get a hold of. I’m quite curious to see the actual article, because, atleast as far as the popular press’s accounts go, this all sounds like old news for anybody whose bothered to visit a library and inspect works older than 1990. In his tremendous work on the pre-Newtonian period of physics from 1950, Dijksterhuis spends a 12 pages addressing da Vinci’s contributions to mechanics and dynamics. While he couldn’t reference the original source material in the same rich way the internet allows today, his conclusions seem very similar and deeper than those being cited in this new work. The science of mechanics in the Middle Ages by Marshall Clagett (1959) also provides an excellent resource putting da Vinci’s work in context, while directly referencing the diagram that everybody seems to be reproducing.

At the moment, I remain of the opinion that da Vinci was an inspiring thinker, participating in the rebirth of interest in the natural sciences during the high renaissance. However, his command of mathematics was weak, and fails in comparison to the likes of Euclid, Hipparchus, Archimedes. While this may only strengthen a certain aspect of his appeal, for me, it is more of an invigorating of a thirst for concreteness. Nicole Oresme remains a much more compelling figure than Leonardo to me (though a much less accomplished artist;)