Population waves

It’s rather accepted knowledge these days that many natural populations rise and fall like waves – sometimes the creatures become more numerous and easy to find (the rise), and then become less numerous and harder to find (the fall). But the history of this as a scientific idea – population waves waxing and waning – is rather incompletely understood.

To begin with, even in old-testament times, variations in common-ness of plants and animals were recognized, particular in the contexts of feast-and-famine, or the irregular arrivals of plague and pestilence. The reasons for these were often mysterious and attributed to curses or acts of gods. For plagues in particular, they were more likely to be attributed to divine intervention than biological phenomena.

Perspectives on systems of living things changed quickly over the time of the second industrial revolution, with the industrialization of hunting and the advancement of infectious disease science. By the 1950’s, it was well-documented that besides human populations, natural populations underwent dramatic changes in their numbers. And although the reasons for particular changes in abundance could still be mysterious at first, it was widely accepted that changes could be explained mechanistically in terms of ecology and environment. So, how did our collective understanding morph from deus ex machina to first principles mechanisms?

In epidemiology, the recent article The shape of epidemics by Jones and Helmreich (2020) traces the idea of epidemic waves back to be in parallel with the development of the germ theory of infectious disease. In 1868, Arthur Ransom explicitly described infectious disease epidemics like measles as progressing like waves over the course of years, with data and charts to back up the description.

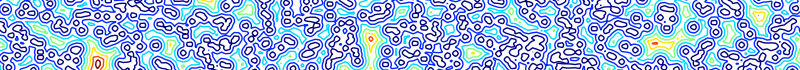

In ecology, this idea has not yet been traced back so far. In 1989, Sinclair reviewed the history of population regulation, and credits the work of Nicholson in 1933 as the start of our modern understanding and soundly within the field we call “ecology” today. But Nicholson himself cited others who had recognized possibilities of both smooth regulation (Like Pearl and Reed 1920,1927) and periodic variation even earlier. The earliest explicit reference to models with oscillation seems to be in Vito Volterra’s citation of changes in numbers of fish in 1926. However, Alfred Lotka had already proposed a theory for changes in population abundance in the form of a system of ordinary differential equations that we now call the Lotka–Volterra equations. He may well have been inspired by his earlier work (1912) hypothesizing oscillatory solutions for Ross’s epidemic theory — hence connecting ecology back to epidemic theory.

That part’s all well-documented today. Yet, Lotka drew part of his inspiration from an even older source than Ransome – a source that seems to have been overlooked so far. In 1860, Herbert Spencer published his 500+ page book “First Principles”, as a foundation for his philosophy. In it, he makes numerous references to the concept of rhythmic variation in population numbers over time. He even goes on to point out that these rhythmic variations need not be perfectly periodic, but may be less regular in their nature with respect to period and amplitude.

This is something that deserves more attention. Spencer is a particularly interesting transitional figure, working in scientific philosophy, but devoid of explicit mathematics and empiricism, in parallel with the developments of germ theory and biological evolution, as well as the emerging social sciences of economics, anthropology, and sociology. Unfortunately, one of his biggests effects was to aid the rise of social darwinism as a cultural movement, which would fester and take malignant form over the next 100 years.